“It’s (food security) the link between all other great global challenges we face. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has brought this into very sharp focus. UN Security General Guterres said it best: Russia is bombing one of the major bread baskets of the world.”

These are the words of Cindy McCain Permanent Representative of the U.S. Mission to the UN Agencies in Rome, while discussing the impact the ongoing Russia/Ukraine war is expected to have on food security in Africa and around the world.

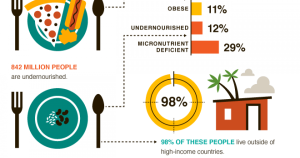

The Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that as many as 13 million more people worldwide will be pushed into food insecurity as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Before Russia invaded Ukraine, the food security context was already concerning due to the lasting COVID-19 impacts, ongoing humanitarian emergencies, high global food prices, and high fertilizer prices.

“Forty percent of wheat and corn exports from Ukraine go to the Middle East and Africa, which are already grappling with hunger. Ukraine itself was a major source of wheat for the World Food Program. WFP is feeding 138 million people in more than 80 countries, including Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Nigeria,” said McCain.

“The truth of the matter is Putin’s war forces us to take from the hungry to feed the starving. As a government, we have invested heavily in resilience-building programs and committed to providing more than $11 billion over the next five years to address food security and nutrition needs worldwide. But Russia alone can stop this global catastrophe we’re facing, and felt – and also being felt on the African continent and beyond,” she added.

With Russia and Ukraine as major suppliers of the world’s exports and agriculture inputs such as fertilizer, the effects of the war are expected to reverberate for years to come.

“Reduced food and supplies and subsequent price increases in these commodities make it harder for farmers in Zambia to access the input they need to plant their crops, and for families in Malawi to buy nutritious food for their children,” according to Dr Jim Barnhart, Assistant to the Administrator in the Bureau for Resilience and Food Security

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

“So if not mitigated, these price increases could result in significant increases in global poverty, hunger, and malnutrition, particularly in regions like sub-Saharan Africa. And from the last global food crisis in 2007 and 2008, we saw the destabilizing effect this can have on international order. During that time, food riots occurred in at least 14 African countries. And even with the release of grain reserves or the cessation of hostilities, the impacts will persist. There will be irreversible effects on food production as farmers lack the resources and inputs to plant their spring and summer crops,” said Barnhart.

Following the food price spikes in 2008, the then US President Barack Obama launched the U.S. Government’s Feed the Future initiative, which is working to strengthen resilience, food systems, agriculture investments, and improved nutrition.

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure: experience has shown that $1 invested in resilience efforts can save up to $3 in humanitarian assistance down the road. So all of this helps to ensure that major shocks like COVID-19, climate change, and conflict are not causing families to slide back into poverty and malnutrition, but able to remain resilient.”

To withstand these shocks, African governments should work towards increasing productivity, getting more per hectare from smallholder farmers that dominate the agriculture sector across the continent.

The US and it’s partners are doing biofortified foods improving nutrition for the foods that are being sold.

“It’s about linking systems so that whether it’s cold storage, roads, et cetera, it’s about investments that make it easier from the seed to the market, that flow of goods moving as quickly and as efficiently as possible,” said Barnhart.

Furthermore, African governments, like the rest of the world, should not close themselves off but instead stay open to trade and allow markets to operate. Governments should also consider to, if needed, reallocate resources to ensure that the most vulnerable are getting nutrition support required and other kinds of basic staples to allow them to get through this period.

“It’s going to be tough,” according to Barnhart.